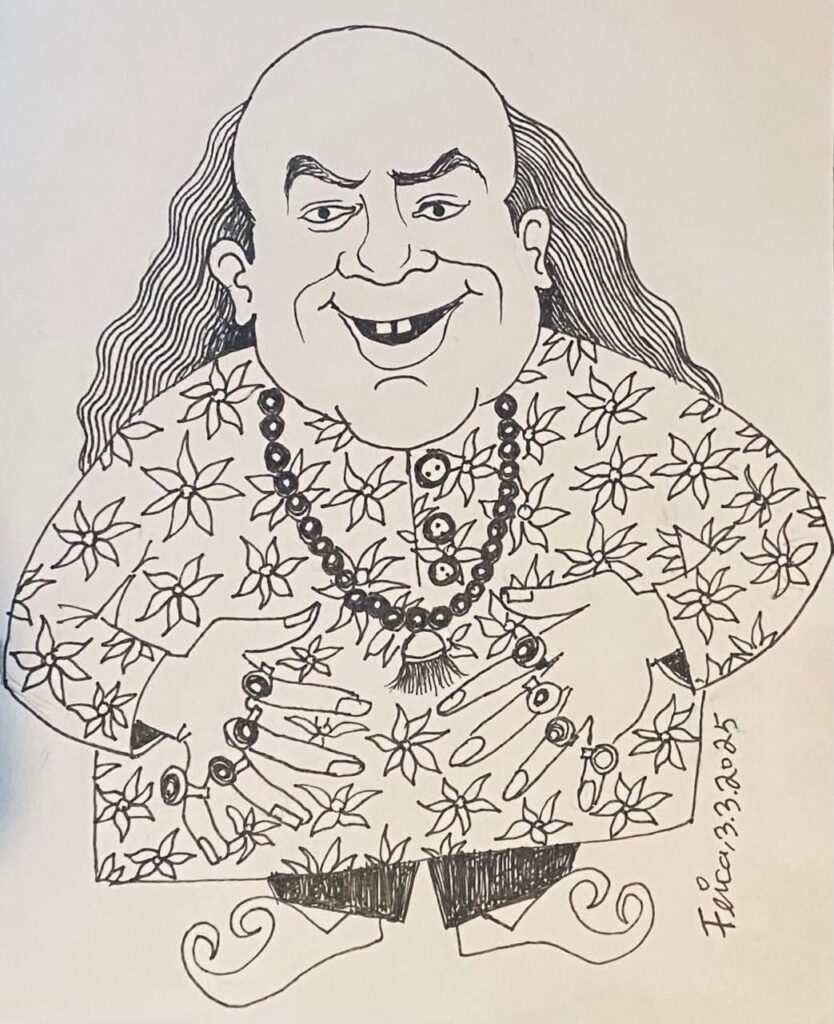

Chahat Fateh Ali Khan: The Bahlul Dana of Our Times

In every era, there emerges a figure who defies the norms of society, mocks the rigid structures of culture, and, in doing so, exposes the absurdity of the world. Often, such individuals are dismissed as fools, yet history remembers them as sages disguised in jesters’ garb. Pakistan, a nation steeped in political turmoil and cultural conservatism, has recently found its own Bahlul Dana in the most unexpected of places: the out-of-tune, off-beat, and unapologetically obtuse Chahat Fateh Ali Khan.

At first glance, Chahat Fateh Ali Khan is an enigma of embarrassment. He cannot sing a tune to save his life. His voice wobbles precariously between misplaced octaves, and his understanding of melody is as absent as democracy in a dictatorship. Yet, he sings with the conviction of a maestro, the passion of a poet, and the unwavering belief of a revolutionary. He embodies everything that classical music abhors—disregard for rhythm, ignorance of notes, and a blatant violation of harmony. But therein lies his genius.

Much like Bahlul Dana, the fabled Abbasid-era wise fool who used his feigned madness to expose the hypocrisy of rulers, Chahat Fateh Ali Khan has unknowingly (or perhaps knowingly) become the mirror that reflects the absurdity of Pakistan’s rigid artistic and political norms. In his comic defiance of music’s sacred rules, he challenges the self-appointed custodians of art, ridiculing their elitist claim to culture. Where others train for years to master the intricacies of classical music, he bulldozes through tradition with the reckless enthusiasm of an untrained child. And yet, the public listens. Not just listens—but roars with laughter, shares his performances, and makes him viral.

His greatness does not lie in his ability to sing, but in his ability to make people laugh at the very things they take too seriously—whether it is the sanctity of music, the illusion of prestige, or the self-importance of an industry that demands reverence. In his hilariously off-key renditions, he forces Pakistanis to embrace an uncomfortable truth: that so much of what we glorify—be it politics, music, or culture—is often just an illusion, a performance, an inside joke that no one dares to laugh at. Until now.

Much like Bahlul Dana mocked the Abbasid caliphate by sitting on the throne and declaring it “a mere piece of wood,” Chahat Fateh Ali Khan mocks the frozen world of Pakistani culture, standing in the midst of its self-proclaimed giants and proving that talent is often secondary to sheer audacity. He is the jester who has become the king, not through mastery, but through defiance. His music, though musically atrocious, is socially profound.

Chahat Fateh Ali Khan is no mere clown; he is a social phenomenon, a postmodern rebel who has unknowingly shaken the frozen political and artistic scene of Pakistan. He does not seek approval; he does not demand legitimacy. Instead, he revels in his own absurdity, daring the world to either laugh with him or be left behind in their stiff, self-serious reality.

In a nation where everything—politics, religion, and art—is treated with suffocating reverence, Chahat Fateh Ali Khan has performed the ultimate act of rebellion: he has made a joke out of it all. And in doing so, he has carved a place for himself in the grand tradition of jesters who were, in truth, the wisest of them all.

Pakistan may not realize it yet, but it has found its modern Bahlul Dana—a man whose voice may be off, but whose impact is pitch-perfect.